“Carmina Burana” is a tremendously popular work featuring interesting timpani and percussion parts, which make it also a well-liked composition among percussionists. This series of articles will deal with the percussion instruments included in the orchestration, a description of them, clarifications about some obscure indications by the composer and assignments.

Benediktbeuern is a municipality in Bayern, Germany. In 1803, a manuscript containing songs and poems from the 13th and 14th centuries was found in its abbey (“Bura Sancti Benedicti” in Latin, “Kloster Benediktbeuern” in German) by Johann Christoph von Aretin.

In 1847, Johann Andreas Schemeller published an edition of the original version, giving it the title of “Carmina Burana” (it was his invention, as that title does not appear in the original Medieval manuscript). “Carmina” (plural) means “poems”, “songs”; “Burana” means “from Beuern”. So, the title means “Songs from Beuern”.

Carl Orff got a copy of the Schemeller edition in 1934. With the help of Michel Hofmann, 24 poems were selected and between 1935 and 1936 “Carmina Burana” was composed. It was premiered on June 8, 1937, at the Städtische Bühnen Frankfurt am Main under Bertil Wetzelsberger.

Having set a historical context, let us start with the timpani part(s). The score manuscript (of which I own a copy) indicates the following:

PAUKEN (5 KESSEL)

That translates as TIMPANI (5 DRUMS). In fact, a strict translation would be 5 KETTLES.

The SCHOTT score indicates the following:

5 TIMPANI (ANCHE UNO PICCOLO)

That indication translates as 5 TIMPANI (INCLUDING A PICCOLO). This is a more detailed indication compared to that in the manuscript.

MAIN PART

Despite the indications above, the main timpani part is playable on four drums (depending on their ranges). With standard sized bowls, we can get a “D” on the second drum, a “G” on the third one and an “A” on the fourth one. This “A-D-G-A” arrangement (with high “G” and high “A” being played in the same number) is only needed in the initial and final O Fortuna, so the whole work is perfectly playable on four drums, as long as the correct sizes are chosen. Playing on four or five drums is up to the timpanist in charge.

The most famous number in “Carmina Burana” is, no doubt, O Fortuna, which is repeated at the end, thus getting us back to the initial point, reinforcing the idea of the turning wheel, completing a full revolution and closing the cycle. This number has developed several interpretations/traditions apart from the published timpani part. There is nothing wrong with playing the ink, but it is good to know what others have done.

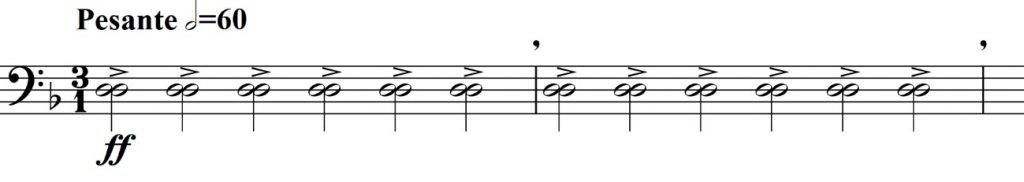

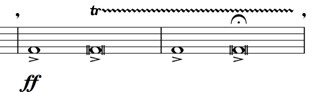

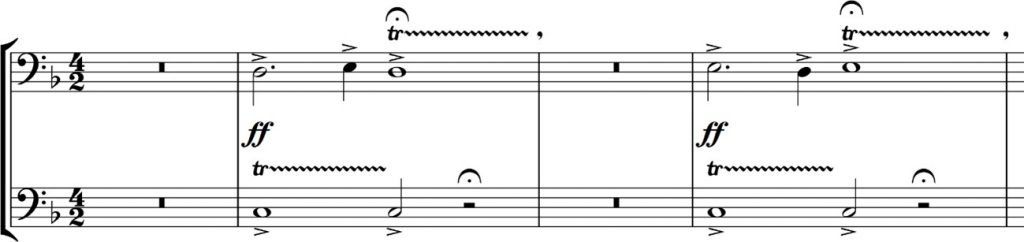

These are the first two bars:

1.- Some timpanists double the “D” on the two middle l drums (check Wieland Welzel). This allows for more volume without forcing the sound.

2.- Other timpanists play the first note of each bar one octave down, adding a dramatic effect.

(This is sometimes done only in the last O Fortuna as a variation of the first one).

3.- A combination of the previous two is also possible. The first note is played one octave lower and the rest are doubled on two drums. Again, doing it in both numbers or just in the final one is up to the performer.

4.- Doubling all the notes in octaves is another option, playing the low note softer.

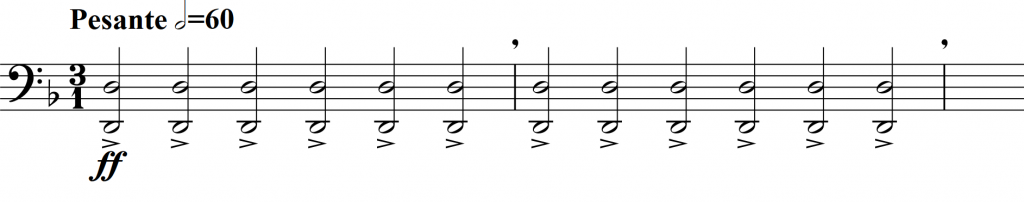

5.- These are the last two bars of the introduction as they appear in the manuscript:

Note the absence of an accent in the penultimate “A”, which perfectly matches the bassoon, contrabassoon, tuba, celli and double bass parts. The manuscript also shows a later addition at this point in the form of diminuendo (only in the timpani part), but I strongly believe that that was something that Orff added for a particular occasion after some rehearsal or performance involving a particularly loud timpanist.

This is how those two bars look in the modern part. Note the presence of the new accent:

The part has changed with the addition of that accent, but the score has not. Yes, it features the accent in the timpani line, but the other instruments (bassoon, contrabassoon, tuba, celli and double basses) still do not feature it, which makes me think that we are in the presence of a misprint in the timpani part and in the score. I believe that it is musically wise to match the parts that we double, so I do not play that penultimate accent.

6.- The first “A” may be doubled on two drums (check the orchestra of La Fenice).

Bear in mind that doubling the “A” on two drums, (if we have doubled the previous “D”s), presents its own challenges in the form of pedaling or adding an extra drum.

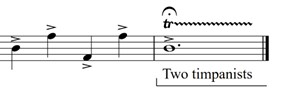

7.- The second timpanist may join for the following roll (a continuous one, the accents being played by the first timpanist only for the sake of precision and clarity. Check the Berlin Philharmonic recording).

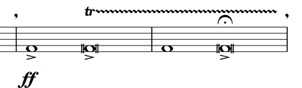

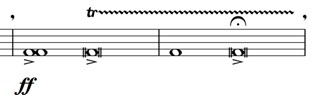

8.- This is the super-famous ostinato one bar after figure 6.

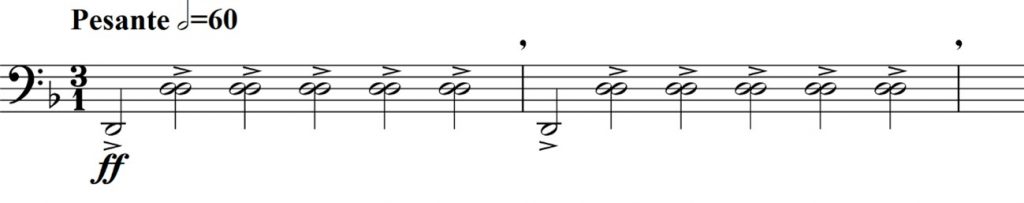

See that all the notes are accented which, to me, presents no musical interest. If everything is accented, nothing really stands out. Everything becomes noisier, but nothing is, in fact, highlighted. Note also that the indicated dynamic is only forte . This is how that passage is written in the manuscript:

Note that only the “D”s and low “A”s are accented. This is much more interesting, as the passage features more dynamic contrast. This also is the justification for a tradition that I have seen; namely, the second timpanist doubling all those accented “A”s and “D”s (check Berlin Phil under Ozawa).

9.- A simplified version of the above is for the second timpanist to double the “A”s and “D”s, in a more assertive way, only when playing together with the bass drum (check the Concertgebouw recording orchestra under Chailly).

10.- The last nine bars are, indeed, accented in both the manuscript and the part. It makes sense, especially as we get closer to the climax. I like how Orff originally wrote fewer accents one bar before figure 6 and then accented all the notes in the coda, building up in intensity.

11.- The final roll is sometimes doubled by both timpanists.

Please remember that all these variations/modifications ARE NOT compulsory; we do not have to play them. The timpani part works perfectly fine as written, but I want you to know what other timpanist have done over the years, what I have seen others play and what I have, depending on the context, played. Use your musicality, good taste and knowledge to modify the part or not. Remember that we are serving the music.

Regarding other numbers in “Carmina Burana”, we can find an interesting indication in No. 5 (Ecce Gratum). Orff indicates harte schlägel (“hard sticks”) four bars before figure 25. This is the only indication in the whole manuscript referring to what sticks are to be used.

Do check the solo together with the flute in number 6, Tanz, as it is exposed and must be rhythmically precise, nice sounding, piano but with projection, have a dance character while being musical and flow with the flute. That passage is often asked for in auditions.

It is interesting to see that, in No. 14 (In taberna quando sumus), Orff changed his mind. His initial intention was for the ostinato “E”s to be offbeat, establishing a “boom-boom dialogue” between the timpani and the low voices (double basses, tuba, bassoon and contrabassoon). In the manuscript we can clearly see that he erased that and, on top of it, he wrote the part as we know it today, namely, on the beat.

SECOND PART

Regarding the second timpani part, it presents no problem whatsoever for orchestras with a timpani section comprising two timpanists or a timpanist plus an assistant timpanist (which both are the case in large and important orchestras). Part 2 is played by the second timpanist or the assistant, usually on a separate set of drums.

If that is not the case, a member of the percussion section moves over to the timpani to play the second part. In this situation the timpanists tend to share drums, but my preference is for a dedicated set assigned to each timpanist. Maybe not the best solution when it comes to logistics or onstage space, but, I prefer two separate sets of timpani, one for each player.

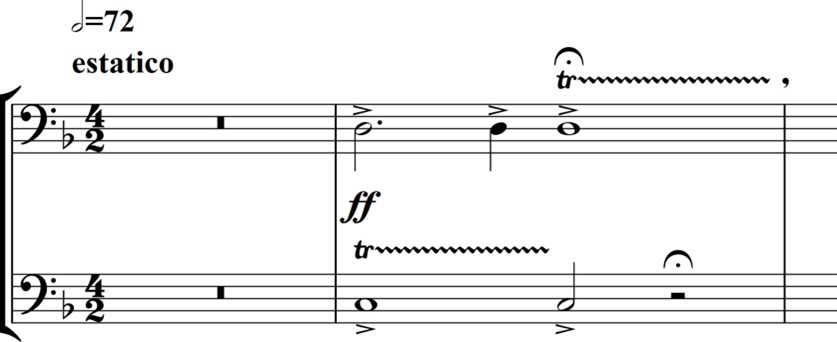

1.- Apart from the doublings outlined in the previous section (which must be decided by the principal), the second timpanist plays in number 7 (Floret silva).

Despite the manuscript part being crystal-clear when assigning the top line to the second timpanist and the bottom one to the first timpanist (specially the manuscript, which uses a bracket to indicate the second part), I have seen Oswald Vogler swap parts. After playing the first bar solo, he plays the high “G”, while the second timpanist plays the “double stops” on the low “G” and the “D”. Something to consider.

2.- The second timpanist also plays in number 24 (Ave Formosissima).

Some timpanists play both parts together without the aid of another player, but, as we already have a second timpanist available (or a colleague from the percussion section), I prefer the “C”s to be played by that second timpanist, as that yields, in my opinion, a much better musical result.

You may want to double the melody in the first timpani part. “D-E-D” the first two times; “E-D-E” the next four times. That is what the other instruments featuring the same rhythmical pattern as we do (dotted quarter, halfnote and whole note) play.

Aside from the case in which the timpanists share drums, the second timpanist will need two instruments: one for the high “G” in Floret silva, another one for the “C” in Ave Formosissima. If the second timpanist is going to double the “A”s and “D”s in both O Fortuna, then he/she will need three drums (the two drums mentioned above plus an extra “A”).

The timpani part and the score are full of discrepancies. Some articulations are missing, some lengths do not match the other instruments, some “solo” indications are incorrect, and there are repetitions in the part (to save space and to make layout easier) that do not exist in the score, etc. Also, there are many differences between the manuscript and the published score and parts (dynamics, articulations, etc.), but that will be dealt with in a future book.

I strongly encourage anyone playing “Carmina Burana” to write his/her own timpani part, as the editor provides a timpani/percussion score featuring non-sense page turns (one would have to turn pages while playing), the score format makes reading inconvenient and it occupies 43 pages when it could take less than half that number.

Stay tuned for more articles dealing with the percussion part of this popular work!

David Valdés started playing piano at the age of seven. He discovered percussion at sixteen and studied both instrumental disciplines for several years but, once he gained his B.Mus. in Piano, percussion became his main interest.

He gained his B.Mus. in Percussion at the Oviedo Conservatory of Music under Rafael Casanova (OSPA), having obtained the “Angel Muñiz Toca” Extraordinary Award and the Principal’s Award. He also gained a B.Mus. in Solfege, Sight Reading and Transposition and has been trained in Chamber Music, Music Theory and Counterpoint.

David attended the Madrid based “Centro de Estudios Neopercusión”, where he studied with Juanjo Guillem (ONE), Enric Llopis (ORTVE), Francisco Díaz (OST), Juanjo Rubio (OCM), Oscar Benet (OCM), Belen López, David Mayoral and Serguei Sapricheff.

He studied at The Royal Academy of Music in London with Andrew Barclay (LPO), Simon Carrington (LPO), Leigh Howard Stevens, Nicholas Cole (RPO), Dave Hassell, Paul Clarvis, Neil Percy (LSO) and Kurt Hans Goedicke (LSO), where he gained his Postgraduate Diploma in Performance (Timpani and Percussion) and his LRAM. He also studied Jazz with Trevor Tompkins, Orchestral Conducting with Denise Ham and Choral Conducting with Patrick Russill.

David has attended many courses and master classes by renowned musicians: Jeff Prentice, Rainer Seegers, Benoit Cambrelaing, David Searcy, Ben Hoffnung, Philippe Spiecer, Enmanuel Sejourné, Keiko Abe, Eric Sammut, She-e Wu, Joe Locke, Anthony Kerr, Dave Jackson, Makoto Aruga, Chris Lamb, Collin Curie, Evelyn Glennie, Mircea Anderleanu, Steven Shick, John Bergamo, Airto Moreira, Birger Sulsbruck, Peter Erskine, Dave Weckl, Bill Cobham, Carlos Carli, George Hurst, Arturo Tamayo, Collin Meters, José María Benavente, Román Alís, Fernando Puchol, Michel Martín, Javier Cámara, Francisco José Cuadrado… These musicians have trained him in Percussion, Piano, Contemporary and Modal Harmony, Jazz, Conducting, Music Production, Editing and Microphone Techniques.

He was awarded the Principality of Asturias Government Scholarship three times in a row, he was finalist at the International Keyboard Percussion Competition sponsored by the Yamaha Foundation of Europe and was runner-up for the Deutsche Bank Pyramid Awards, given to innovative performance and composition projects.

David has played with the following orchestras: Gijón Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Principality of Asturias Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Oviedo Filarmonía (Spain), Asturias Classical Orchestra (Spain), Spanish National Orchestra (Spain), Catalonian Chamber Orchestra (Spain), Castilla y León Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Orchestra of the University of Oviedo (Spain), City of Avilés Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Moscow Virtuosi (Russia), Concerto München Sinfonieorchester (Germany), WDR Rundfunkorchester Köln (Germany), Arthur Rubinstein Philharmonic Orchestra (Poland), Orquestra do Norte (Portugal) and the Ulster Orchestra (UK). He has also played with early music ensembles (Forma Antiqva, Memoria de los Sentidos, Sphera Antiqva and Ensemble Matheus), and chamber groups (RAM Percussion Group, Neopercusión and Ars Mundi Ensemble).

He has translated into Spanish “Method of Movement for Marimba” (L. H. Stevens), the internationally acclaimed book used in conservatoires and universities worldwide. He is, also, the Spanish translator of www.percorch.com, the website used by many orchestras to organize their percussion sections. He is currently working on a new critical edition of the percussion part of “Histoire du Soldat” and on 19th century repertoire for fortepiano and tambourine.

He has taught at the Gijón and Oviedo Conservatories of Music. His discography includes many different genres, and he has worked as a session musician, arranger and online instrumentalist as the result of his interest in recording, sound and technology. David is a busy timpani/percussion freelancer and runs his own business: “Producciones Kapellmaister”.

Leave a Reply