CARMINA REVEALED (part 2)

Orff wrote the names of the instruments in German in the manuscript (of which I own a copy). He indicated the following:

Pauken (5 kessel)

Schlagwerk (5 spiele), 2 kleine Trommeln, 1 grosse Tromel,1 Schelle, 1 Triangel, 1 paar Cymbeln, 2 paar Becken, 1 grosser Gong in D

1 kleiner Gong (oder Glocken platten immer in No.13)

3 Glocken in F C F

Röhrenglocken, 3 Glockenspiele, 1 Xylophone, 1 Castagnette, 1 Ratschen

On December 1950 (thirteen years after the premiere!), preparations for a printed score start. On July 1951 (note how slow things were moving), Orff indicated that “All the instrumental descriptions in the score will be in Italian […]. I do not know the Italian name for some of the instruments and cannot find them in any dictionary. Perhaps you could obtain them from Carisch or somewhere else […]. It is urgent to the extent that some instrumental descriptions are needed at the end of the vocal score […]. In any case, no German descriptions except for Glockenspiel, that is to be found described thus in all international scores, also in Italian ones […]”.

Almost two months later, another letter indicates that nothing was solved about the Italian terms in “Carmina Burana”. The following is stated: “Orff is just going through the corrections of the Burana score and in this connection asks you some questions (the descriptions will all be Italian) […]. We would be very grateful if you could discover the authentic expression and descriptions, probably best from Carisch”.

So, between July and September, 1951, no one at Schott nor at Carisch was able to solve the issue regarding the Italian terms (the delays seem to be a constant with “Carmina”).

Still more than one year had to pass by (November 21, 1952) before Orff could have two copies of the final printed conductor score. That conductor score includes the names of the percussion instruments in Italian, but we do not know who translated the German terms. Was it someone at Schott?, someone at Carisch?

The Italian translation is correct (but misses vital information in a couple of entries). The problem is that present-day percussionists tend to be overly-literal (and that, sadly, applies also to music making, but that is a whole different story), and the Italian terms, although correct in general, raise doubts when they are read strictly and literally. If we add to that that the vocal score, just as the conductor score, contains a mere list of the instruments (but not detailed descriptions apart from a couple of pictograms), it is quite natural for percussionists to doubt, as the indications are not unmistakable, positive and definitive when reading to the letter.

This second article (and the upcoming ones) will try to shed light into the dark corner that some of the percussion instruments in this popular work of the repertoire are.

SNARE DRUM

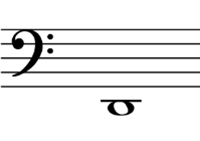

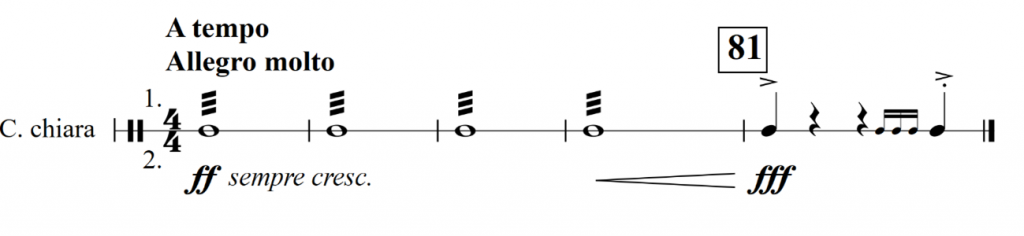

The indication in the manuscript is 2 kleine trommeln. Both the conductor and the vocal score indicate 2 Casse chiare. The translation is correct and offers no doubt: two snare drums are requested in “Carmina Burana”. The second snare drum is played only in number 10 (Were diu werlt alle min), four bars before figure 81.

The percussion score, carelessly written, indicates, due to a system change, to play both snare drums together one bar later than it should really be (three bars before figure 81 instead of four). That is an obvious misprint which is easily solved using musical and common sense (be ready, those of you who stubbornly play the ink!). The manuscript and the conductor score correctly indicate both drums to play a due since A tempo. Allegro molto.

The purpose of two snare drums being used at this point is clear; namely, to get the fullest possible sound in that roll and to get to the loudest dynamic in the whole work, an accented fff.

There are two different approaches when it comes to doubling that roll.

1.- To use two identical drums and heads (or as similar as possible) to get the most similar possible sound, timbre and character.

2.- To use dissimilar drums and heads to get a richer and more varied sound.

Both approaches are valid. The decision is up to the section principal.

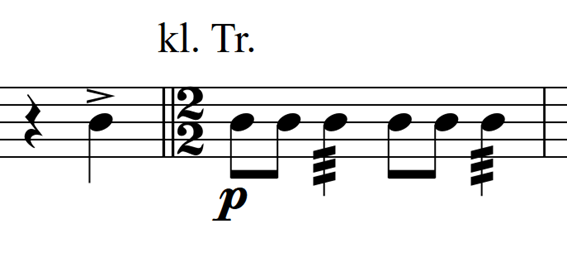

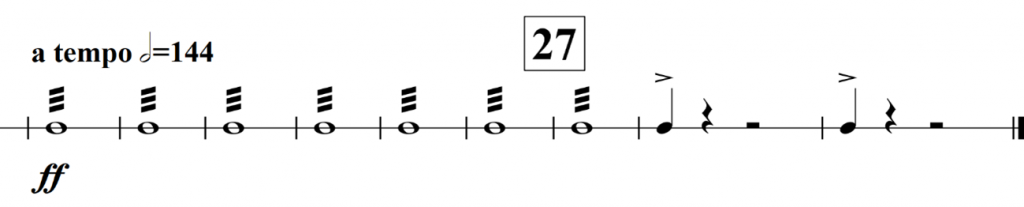

No. 2 (Fortune plango vulnera) features an interesting passage, often asked for in auditions.

Being alla breve and più mosso than the initial half note=120, those rolls are fast. I play them alla Pique Dame: a single stroke with my right hand followed by a buzz with my left one.

This number features many discrepancies between the manuscript and the conductor score in terms of articulation. Also, Orff initially had a different idea regarding the snare drum part. It can be seen very clearly in the manuscript how he erased the old version and wrote a new one on top of the erased one. These two very interesting points will be discussed in a future book.

Regarding No. 18 (Circa mea pectora), a careless transcription from the manuscript to the printed score and part has resulted in an incorrect snare drum part which has been, sadly, perpetuated. In the manuscript, the snare drum and the bass drum share the same staff.

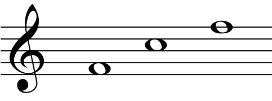

Not only that. Orff used the same line to write both instruments: the third one (big mistake if you ask me). At least he very clearly indicated the name of the instrument always BEFORE the corresponding note (and that is a constant in the whole manuscript, which is of great help to those studying the instrument assignations). Here we have the bass drum in the second bar of this number:

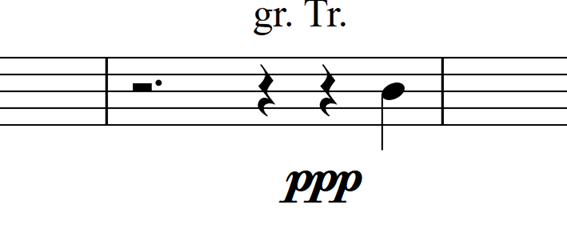

Here we have bar number 11 (figure 119), where the bad transcription occurs:

We can clearly see that the bass drum phrase ends at figure 119 (more on this will be discussed on the article dealing with the bass drum part) and, as always, Orff writes the indication for the new instrument BEFORE it makes its entrance:

So, the accented quarter-note still belongs to the bass drum (together with the suspended cymbal, but that will be discussed in the corresponding article). The snare drum does not make its entrance until the second bar of figure 119, doubling the melody in the choir (Manda liet, manda liet, min geselle chumet niet).

That makes total musical sense: the bass drum and the suspended cymbal double the double basses during the previous phrase and, when a new phrase appears (in a new time signature, tempo and dynamic), the orchestration changes too with the addition of the snare drum rhythmically doubling the choir. The accented quarter-note being assigned to the snare drum, which is a clear miss-transcription from the manuscript to the score and part, destroys that effect “by anticipation”. That quarter-note clearly belongs, as per Orff´s own indication, to the bass drum and suspended cymbal, not to the snare drum, which makes its entrance, together with the xylophone (see the corresponding change in color in the orchestration?) not until two bars after figure 119.

Apart from this obvious blooper by the copyst, this number and No. 22 (Tempus est ioucundus) feature very nice accompaniments doubling the melody. Listen to the instruments playing it and match their articulation, phrasing and dynamics. Remember: the melody is always right!

In general, the snare drum part in “Carmina Burana” is not difficult. It is plagued, indeed, with many discrepancies when compared to the manuscript and the score (not to mention some crazy page turns). I strongly recommend that you check with the score to match the dynamics and articulations of the other instruments we play with.

TAMBOURINE

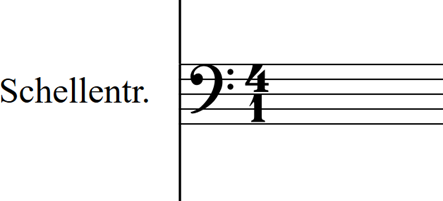

Surprisingly, the tambourine is not mentioned in the list of instruments in the manuscript. It appears for the first time in No. 5 (Ecce gratum):

Schellentrommel means, literally, “jingle drum”. That is a perfectly valid and correct German word for “tambourine”. Both the conductor´s score and the vocal score translate it as Tamburo basco, which is correct. It is mentioned, yes, in the list of instruments in said editions (remember, not in the manuscript).

Nothing obscure about the term Schellentrommel. There is no need to split hairs searching for an arcane instrument. Use a tambourine and you will be using the instrument that Orff wanted. Of course, you can use as many tambourines as you consider to adequate the character of the different numbers.

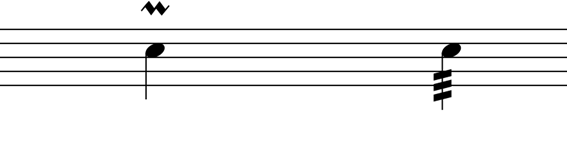

Regarding the roll, the composer uses two clear and distinctive indications: a thrill and slashes.

In general, the slashes are used on long notes, while the thrills are used on short ones. In my opinion, Orff´s writing is very clever and entails two different types of rolls: the thrill for a finger roll and the slashes for a shake roll. If we are going to honour that difference, we must pay attention to No. 7 (Floret silva).

That makes for nice changes in colour and character. I have played No. 7 using two different rolls and everybody was happy and gay.

Having said that, that writing using trills in consecutive notes (see No. 5, Ecce gratum) reminds me of the one used by Elgar in his “Cockaigne Overture”:

My teacher at the Royal Academy in London (Andy Barclay, principal for the London Philharmonic) taught me to play that passage with the tambourine in a totally vertical position (to get as much ringing from the jingles as possible) and to hit it with the hand (that is what battuto col mano means in Italian) on the center of the head. His literal words were “in a Salvation Army style”. Orff never indicated what the slashes and the trills mean, so we, interpreters and not mere readers, are free to choose whatever colour we might think that suits the musical context best. At the end of the day (and contrary to what would happen should we were heart surgeons) no one dies because of our music-making decisions, and that “Salvation Army colour” is one that I have tried and that no one complained about (very much the contrary!). Be musical and imaginative!!

Also in No. 5 (Ecce gratum), some principals ask for the long, loud rolls six bars before figures 27, 31 and 35 to be doubled. You can use two tambourines, one in each hand, or involve another player in the section.

TRIANGLE

The manuscript indicates 1 Triangel. Both the conductor´s score and the vocal score indicate Triangolo in Italian, which is a perfect translation that presents no problem whatsoever.

Apart from the usual discrepancies when compared with the manuscript (articulations, dynamics, etc.), the triangle part is very acceptable in terms of edition.

Do check No. 3 (Veris leta facies), as the part is exposed and the attacks together with the woodwinds should be surgically precise. Watch out for the tenuti.

Be careful, too, with the pianissimo rolls in No. 9 (Reie), as they are extremely delicate.

In general, the triangle part is a good chance to show musicianship, delicacy and a variety of colors.

Stay tuned for the next article in the “Carmina Burana series”.

David Valdés started playing piano at the age of seven. He discovered percussion at sixteen and studied both instrumental disciplines for several years but, once he gained his B.Mus. in Piano, percussion became his main interest.

He gained his B.Mus. in Percussion at the Oviedo Conservatory of Music under Rafael Casanova (OSPA), having obtained the “Angel Muñiz Toca” Extraordinary Award and the Principal’s Award. He also gained a B.Mus. in Solfege, Sight Reading and Transposition and has been trained in Chamber Music, Music Theory and Counterpoint.

David attended the Madrid based “Centro de Estudios Neopercusión”, where he studied with Juanjo Guillem (ONE), Enric Llopis (ORTVE), Francisco Díaz (OST), Juanjo Rubio (OCM), Oscar Benet (OCM), Belen López, David Mayoral and Serguei Sapricheff.

He studied at The Royal Academy of Music in London with Andrew Barclay (LPO), Simon Carrington (LPO), Leigh Howard Stevens, Nicholas Cole (RPO), Dave Hassell, Paul Clarvis, Neil Percy (LSO) and Kurt Hans Goedicke (LSO), where he gained his Postgraduate Diploma in Performance (Timpani and Percussion) and his LRAM. He also studied Jazz with Trevor Tompkins, Orchestral Conducting with Denise Ham and Choral Conducting with Patrick Russill.

David has attended many courses and master classes by renowned musicians: Jeff Prentice, Rainer Seegers, Benoit Cambrelaing, David Searcy, Ben Hoffnung, Philippe Spiecer, Enmanuel Sejourné, Keiko Abe, Eric Sammut, She-e Wu, Joe Locke, Anthony Kerr, Dave Jackson, Makoto Aruga, Chris Lamb, Collin Curie, Evelyn Glennie, Mircea Anderleanu, Steven Shick, John Bergamo, Airto Moreira, Birger Sulsbruck, Peter Erskine, Dave Weckl, Bill Cobham, Carlos Carli, George Hurst, Arturo Tamayo, Collin Meters, José María Benavente, Román Alís, Fernando Puchol, Michel Martín, Javier Cámara, Francisco José Cuadrado… These musicians have trained him in Percussion, Piano, Contemporary and Modal Harmony, Jazz, Conducting, Music Production, Editing and Microphone Techniques.

He was awarded the Principality of Asturias Government Scholarship three times in a row, he was finalist at the International Keyboard Percussion Competition sponsored by the Yamaha Foundation of Europe and was runner-up for the Deutsche Bank Pyramid Awards, given to innovative performance and composition projects.

David has played with the following orchestras: Gijón Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Principality of Asturias Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Oviedo Filarmonía (Spain), Asturias Classical Orchestra (Spain), Spanish National Orchestra (Spain), Catalonian Chamber Orchestra (Spain), Castilla y León Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Orchestra of the University of Oviedo (Spain), City of Avilés Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Moscow Virtuosi (Russia), Concerto München Sinfonieorchester (Germany), WDR Rundfunkorchester Köln (Germany), Arthur Rubinstein Philharmonic Orchestra (Poland), Orquestra do Norte (Portugal) and the Ulster Orchestra (UK). He has also played with early music ensembles (Forma Antiqva, Memoria de los Sentidos, Sphera Antiqva and Ensemble Matheus), and chamber groups (RAM Percussion Group, Neopercusión and Ars Mundi Ensemble).

He has translated into Spanish “Method of Movement for Marimba” (L. H. Stevens), the internationally acclaimed book used in conservatoires and universities worldwide. He is, also, the Spanish translator of www.percorch.com, the website used by many orchestras to organize their percussion sections. He is currently working on a new critical edition of the percussion part of “Histoire du Soldat” and on 19th century repertoire for fortepiano and tambourine.

He has taught at the Gijón and Oviedo Conservatories of Music. His discography includes many different genres, and he has worked as a session musician, arranger and online instrumentalist as the result of his interest in recording, sound and technology. David is a busy timpani/percussion freelancer and runs his own business: “Producciones Kapellmaister”.

Leave a Reply