by David Valdés

In the previous article we got to know the tambourine part of the “Polovtsian Dances” was written by Glazunov and not by Borodin. We now can pull the thread to try to figure out the meaning of that notation and the technique it entails.

Neither the 1888 Belaieff´s score (or any subsequent reprints -Kalmus, Edition Musicus New York…-) nor the particella of “Prince Igor” indicate the meaning of that special notation in the “Polovtsian Dances”. The same happens with the 1890 Belaieff´s score (the only existing edition, now long out of print) and the particella of “Rapsodie Orientale” (the other work by Glazunov featuring that particular notation for tambourine). The latter two neither indicate the meaning of the symbols above the notes in the cymbal part (suspended, crashed… This issue has already been covered in a couple of articles by truly yours). This makes the author believe Glazunov was working directly with his percussionists, that this technique was a well-known Russian one and that there was no need for the composer to clarify it, as the performers already knew how to play the part (exactly the same with the suspended/crashed cymbals notation). We must find, then, the solution for this puzzle somewhere else…

Glazunov, who was a professor at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory (he was its director for some time), got deeply impressed by the talent of a very young Prokofiev, so he convinced Sergei´s mother to apply to enter said institution. Prokofiev passed the exams and joined the Saint Petersburg Conservatory at 13. Although Glazunov was not Prokofiev´s teacher, the former was highly respected and was the director of the Conservatory, so he had a deep influence on how composition was taught.

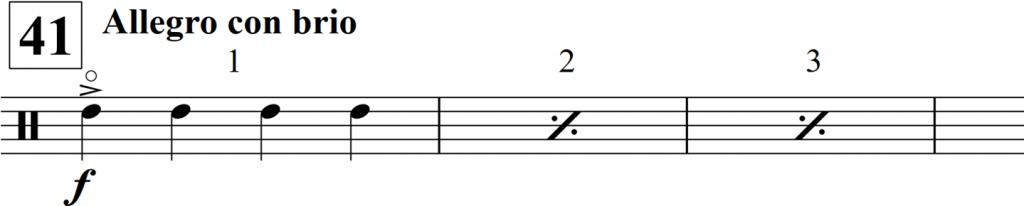

In his famous “Lieutenant Kije” suite, number 4 (“Troika”), Prokofiev uses exactly the same notation Glazunov used in “Rhapsodie Orientale” and in the “Polovtsian Dances”. Where did he learn that notation? Obviously at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, where Glazunov was a composition professor. That notation tradition passed from teacher to student and a new generation of composers started using it:

The A. Gutheil (S&N Koussevitzky) edition gives these very clear instructions in the Kije part: “Les notes munies du signe ‘o’ doivent ètre frappes. AIlleurs secouer l´instrument” (“The notes with the symbol ‘o’ must be struck. Elsewhere shake the instrument”).

Circles are also to be found in the reprint by Kalmus (no instructions are given in this edition. No surprise, right…?).

The preface to the Boosey & Hawkes score (HPS 663; B. & H. 16697) states the following in English, French and Russian:

“In the part of the tambourine (No. 4) the sign ‘o’ above the note means a blow with the fist, while notes without ‘o’ mean shakes”.

“Dans la partie du tambour de basque (No. 4) le signe ‘o’ sur la note signifie un coup de poing, tandis qu´aux notes sans ‘o’ il faut secour”.

Everything is clear now, as instructions cannot be more precise. We have stablished a clear relationship between “Polovtsian Dances”/“Rapsodie Orientale” and a “lineage” of that notation (and the technique it entails) from Glazunov to Prokofiev (the composer who clearly indicated what that notation means).

How is the part in the “Polovtsian Dances”, “Rhapsodie Orientale” and “Lieutenant Kije” played? Shaking the tambourine back and forth and hitting it against the palm (or the fist, or the fingers…That will depend on the dynamics and the sound we want) of the contrary hand when indicated (“o”). The following video features Dances #8 and #17:

Contemporary orchestral tambourine technique has, sadly, evolved neglecting traditional techniques. We, as contemporary percussionists, learn to play the tambourine using modern techniques (sometimes mere “tricks” to avoid learning proper technique and language), not knowing how tambourines and frame drums have been played for generations (the way they were played at the time the masterworks featuring tambourine were written) and neglecting the long tradition frame drums treasure. Because frame drums are simple instruments intended to be played not always by professional orchestral musicians (they have been played by the people for thousands of years), the techniques involved are always logical and relatively easy to master (we do not have to spend 10 hours a day for twelve years to develop a decent technique), so the traditional and historical techniques are easy to learn and can be used to play ANY excerpt of the symphonic repertoire with ease, logic and musicality. If we learnt traditional and historical techniques, we would not need robotic, awkward or alien techniques that, in most cases, are only a patina to cover the lack of knowledge of the tradition: everything is contained in the tried-and-true techniques that have proved their value for millennia.

We now know how to play the tambourine part of the “Polovtsian Dances” but, why do so many percussionists not know how to play this excerpt? Because we tend to compartmentalize styles and to assign this particular technique to orchestral, this other one to pop, that one to folk, that one to early music… We lack imagination, inventiveness and knowledge of the tradition to solve easy musical and technical problems. The “pop tambourine” thing (an easy, logical and musical one), already known by Glazunov and familiar to all Russian percussionists, has been neglected by generations of orchestral percussionists simply because we associate it with a pop context, not with an orchestral one, but it has been there for centuries. Use whatever technique (gospel, pop/rock, Salvation Army, Spanish, Italian, North African, Eastern, historical, contemporary…), no matter where it comes from, to play the tambourine, to make music and to fit a particular context. Playing the tambourine parts using the proper techniques, we will get the sound, character, phrasing, dynamics, richness, variety and “substance” the composers had in mind when writing these works.

I encourage you to learn traditional and historical techniques (which can be used in every orchestral excerpt, as those were the techniques used at the time the masterworks were written!!), to get out of the frame of the rather constricted orchestral techniques and to use your imagination, common and musical sense to make music in the most beautiful possible way.

David Valdés started playing piano at the age of seven. He discovered percussion at sixteen and studied both instrumental disciplines for several years but, once he received his Bachelor of Music in Piano, percussion became his main interest.

He earned his Bachelor of Music in Percussion degree at the Oviedo Conservatory of Music under Rafael Casanova (OSPA), obtaining the highest marks (“Angel Muñiz Toca” Extraordinary Award and “Final Degree” Award). He also gained a degree in Solfege, Sight Reading and Transposition. He also has been trained in Chamber Music, Music Theory and Counterpoint.

David attended the Madrid based “Centro de Estudios Neopercusión”, where he studied with Juanjo Guillem (ONE), Enric Llopis (ORTVE), Francisco Diaz (OST), Juanjo Rubio (OCM), Oscar Benet (OCM), Belen López, David Mayoral and Serguei Sapricheff. He studied at The Royal Academy of Music in London with Andrew Barclay (LPO), Simon Carrington (LPO), Leigh Howard Stevens, Nicholas Cole (RPO), Dave Hassell, Paul Clarvis, Neil Percy (LSO) and Kurt Hans Goedicke (LSO), where he gained his Postgraduate Diploma in Performance (Timpani and Percussion) and his LRAM. He also studied Jazz with Trevor Tompkins, Orchestral Conducting with Denise Ham and Choral Conducting with Patrick Russill.

David has attended many courses and master classes by renowned musicians: Jeff Prentice, Rainer Seegers, Benoit Cambrelaing, David Searcy, Ben Hoffnung, Philippe Spiecer, Enmanuel Sejourné, Keiko Abe, Eric Sammut, She-e Wu, Joe Locke, Anthony Kerr, Dave Jackson, Makoto Aruga, Chris Lamb, Collin Curie, Evelyn Glennie, Mircea Anderleanu, Steven Shick, John Bergamo, Airto Moreira, Birger Sulsbruck, Peter Erskine, Dave Weckl, Bill Cobham, Carlos Carli, George Hurst, Arturo Tamayo, Collin Meters, José María Benavente, Román Alís, Fernando Puchol, Michel Martín, Javier Cámara, Francisco José Cuadrado… These musicians have trained him in Percussion, Piano, Contemporary and Modal Harmony, Jazz, Conducting, Music Production, Editing and Microphone Techniques.

He was awarded the “Principality of Asturias Government Scholarship” three times in a row, he was finalist at the “International Keyboard Percussion Competition” sponsored by the “Yamaha Foundation of Europe” and was runner-up for the “Deutsche Bank Pyramid Awards”, given to innovative performance and composition projects.

David has played with the following orchestras: Gijón Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Principality of Asturias Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Oviedo Filarmonía (Spain), Asturias Classical Orchestra (Spain), Spanish National Orchestra (Spain), Catalonian Chamber Orchestra (Spain), Castilla y León Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Orchestra of the University of Oviedo (Spain), City of Avilés Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Moscow Virtuosi (Russia), Concerto München Sinfonieorchester (Germany), WDR Rundfunkorchester Köln (Germany), Arthur Rubinstein Philharmonic Orchestra (Poland), Orquestra do Norte (Portugal) and the Ulster Orchestra (UK). He has also played with early music ensembles (Forma Antiqva, Memoria de los Sentidos, Sphera Antiqva and Ensemble Matheus), and chamber groups (RAM Percussion Group, Neopercusión and Ars Mundi Ensemble).

David has translated into Spanish “Method of Movement for Marimba” (L. H. Stevens), the internationally acclaimed book used in conservatoires and universities worldwide. He is, also, the Spanish translator of www.percorch.com, website used by many orchestras to organize their percussion sections.

He has taught at the Gijón and Oviedo Conservatories of Music. His discography includes many different genres, and he has worked as a session musician, arranger and on-line instrumentalist as the result of his interest in recording, sound and technology. David is a busy timpani/percussion freelancer and runs his own business: “Producciones Kapellmaister”.

David Valdés enjoys sailing, windsurfing, snowboarding, rollerblading, reading, and playing with his two daugthers: Carmen and María.

LEARN MORE ABOUT DAVID AT: David-Valdes.com

Leave a Reply